A fighting chance

By Jasmina Chatani

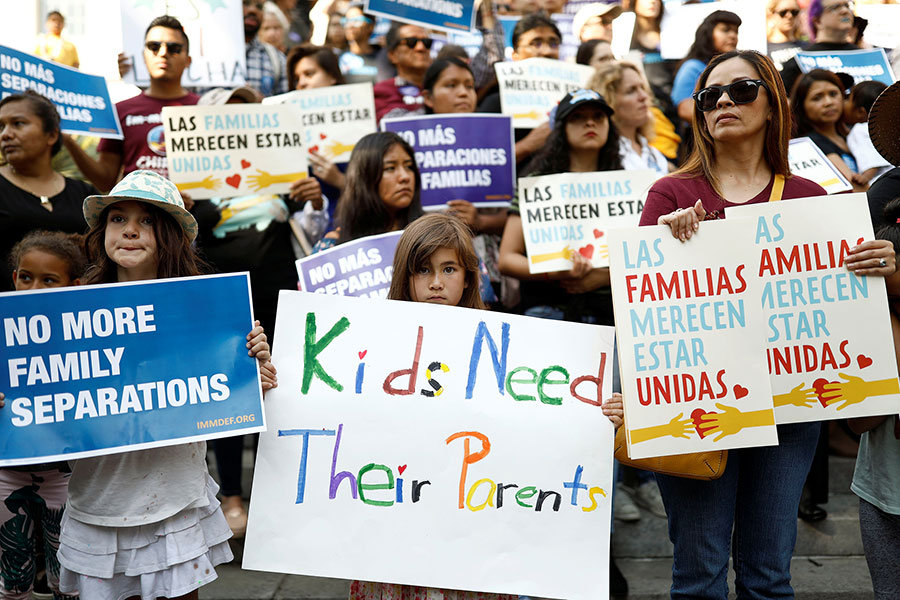

Adults and children protest recent family separations of arriving immigrants at an outdoor demonstration.

Last month, federal immigration agents separated a 10-year-old girl with Down syndrome from her mother at the border. Nine months before that, agents did the same to a 16-year-old boy with autism, taking him from his caregiver grandmother.

Unimaginably unconscionable, their separations and those of some 2,300 other children at the border from their parents and other caregivers came in the wake of president Trump’s zero tolerance policy against immigrants allegedly entering the country illegally. Though the president eventually signed an executive order June 20 calling for children to instead be detained with their families through the duration of immigration proceedings, the damage is done.

“Decades of psychological research show that children separated from their parents can suffer severe psychological distress, resulting in anxiety, loss of appetite, sleep disturbances, withdrawal, aggressive behavior and decline in educational achievement,” noted The American Psychological Association the day of the president’s executive order.

Children’s development can be further impacted. Other health experts note that when children are separated from their parents, their stress hormones become over-activated. This can lead to slower development of speech and motor skills. Or problems with memory, attention and the capacity to regulate emotions. For some children, these unfortunate circumstances could lead to the development of such impairments as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder.

As a budding school psychologist, I soon will be tasked with the responsibility of supporting the emotional, social and academic needs of children, both with and without disabilities, in educational settings. I wonder how my responsibilities – and the responsibilities of other support professionals in our nation’s schools – will become more complex – more intense – should we connect with some of these children down the road. Will they be able to attend school regularly or will they experience feelings of fear and anxiety from being away from their family for an entire school day? Will they act out in class because they don’t trust the adult in the room? Will they drop their head, sullen and withdrawn, if I and other mental health professionals attempt to talk with them about how they’re feeling? The answers aren’t known.

What is known is that these children already have experienced trauma that will likely have lifelong implications. And for thousands, the ordeal is far from over. About a week after the signing of the president’s executive order, a federal judge in California ordered immigration authorities to reunite separated families within 30 days. For children younger than five, they were to be reunited before 14 days. The government missed the first two-week deadline. It since has shared that it has reunited half the children younger than five with their parents following criminal background checks and DNA tests on the remaining parents to ensure the safety of the children upon reunification.

Enough already. To enhance the well-being of children separated from their parents and other caregivers at the border – to give them a fair or a fighting chance at healing – reunite them with their families without delay.

Categories: civil rights, Down syndrome, intellectual Disabilities, people with disabilities, physical disabilities, politics, Uncategorized